The symbol of the bull has been held sacred, mighty, interesting, full of mystery, and very present in artwork for centuries. Throughout history its meaning has remained the same, and in the context of each culture been able to represent different forms of both power and fertility. Art is a fundamental factor in the preservation of this symbol. If not for Sir Arthur Evans discoveries in Crete, or the presence of Minoan artwork in world trade, the symbol of the bull may have remained a secret of the past. Though the presence of the bull in society has changed drastically, it still has an omni-presence in our world to this day. The good we create from the bull are widely used every day and therefore contributing to our well-being. While we no longer believe the bull has control over the weather, we do understand it has control over our stock market with phrases like “bull and a bear market.” The symbol may have a new platform, however it still holds strong as a symbol of power.

Pablo Picasso (among others) has explored the symbol of the bull quite extensively in his artwork. In fact, he has produced so much artwork related to the myth of the bull that there are books written solely on his exploration of the bull. In order to understand how Picasso interpreted the bull, we must first understand how he came to be aware of the bull, and what it meant to the culture that introduced it to him.

Pablo Picasso (among others) has explored the symbol of the bull quite extensively in his artwork. In fact, he has produced so much artwork related to the myth of the bull that there are books written solely on his exploration of the bull. In order to understand how Picasso interpreted the bull, we must first understand how he came to be aware of the bull, and what it meant to the culture that introduced it to him. The image of the bull has always been a prominent one in Spain. Believed to be Cretan influence, the image of the bull has been on Spanish coins as homage to their mythological presence in cultural history. The first well-defined coins on which a bull appears seem to have a Greco-Roman influence. These coins come from the Balearic island of Ibiza and the city of Sagunto on the east coast of Spain. The presence of bull fights in Spanish culture can be speculated as a Roman influence; however the likelihood of this influence does not seem to be valid. This is due to the timing and the stylistic differences. It is more likely that, if anyone, the Cretans would have introduced the concept of bull games to the Spanish when trading with the islands of the Balearic.(Marrero pp 3-30)

In Spain, the ceremony of beheading the bulls at the end of the hunt was recreated for public entertainment. These events were called the taurobolius or bull hunts. A special dagger was used to sacrifice the bull and then the blood of the bull, still warm, would be poured over “initiates.” Initiates to what? I don’t know. These ceremonies seemed to end around 390, and from them the modern bullfight arises. Though the ceremonial aspects of these seem to be lost in the modern interpretations, this in shows that what happens today still carries with it myth and spirituality even if it is currently unaware.

This is where Picasso thrives. According to Marrero there is a constant duality of dark and light in the Spanish myths. This is a very big part of Picasso’s work, and it is evident that his interest in bulls is rooted in the mystery of the bull. This is shown in an etching Picasso made entitled Minotauromachy in which the minotaur shields itself from the light which comes from a candle held by a child. (Blunt pp 24)

|

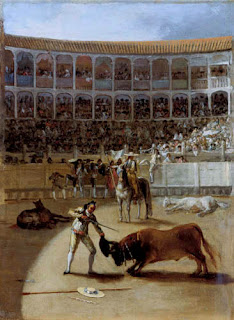

| Goya's The Matador kills the bull |

This contrasts what Picasso’s predecessor Goya was showing in his art about bulls. Goya made a series of etchings and paintings glorifying the many stories of the bull fight, usually set in the arena with the toreadors dressed in full flamboyant garb. He did showcase the light and dark aspect of a bull fight, which must have interested Picasso. There were two reasons for this; the first, and practical being that there were literally two types of seats available at the corridas one in sunlight and one in shade, the other, more metaphoric significance would be the beauty of the bull fight in the light and the death and ugliness of this act would be in the darkness. Picasso’s interest laid in the myth and unspoken spirituality of the bull in the same arena. Or, in other words in the shadow and darkness of the arena. He was interested in the myths that began the bull fights, not glorifying the senseless pastime of the act. This is evident in his etching Minotauromachy. (Marerro pp 51-54)

|

| Minotauromachy by Picasso |

|

| The variety of Picasso's artistic explorations of the bull |

Picasso's work focusing on bulls is very extensive. He explored the bull in many different forms of art. This could be seen as the pride of a Spaniard, or the struggle with the beautiful and the ugly in the presence of the same animal or persona. Whatever the reason he explored this animal in etchings, drawings, paintings, sculpture, through realism, cubism, purely line, simplistically, etc. The series of lithographs in which Picasso explores the simplest form of the bull, it is intriguing that he shows the bull with a large body and exaggerates the small head. This speaks for the bull's actions, being no thought and all force, it can also be seen as a psychological interpretation of the inner bull we all face.

I wanted to discuss Picasso in order to show how his artwork has helped in a re-introduction of the bull into our modern society. Picasso’s imagery still enters our everyday lives, and his influence cannot be overlooked when discussing art in the twenty first century. Many symbols have been forgotten and resurrected throughout history and the symbol of the bull has held its ground throughout many civilizations. Picasso was able to examine the bull in a way that allows us to admire both its beauty and its ugliness. We cannot help but recall the many myths we learned about as a child when we see imagery of a minotaur in his art. He consciously shows the bull’s history when creating a new image of the bull.

I wanted to discuss Picasso in order to show how his artwork has helped in a re-introduction of the bull into our modern society. Picasso’s imagery still enters our everyday lives, and his influence cannot be overlooked when discussing art in the twenty first century. Many symbols have been forgotten and resurrected throughout history and the symbol of the bull has held its ground throughout many civilizations. Picasso was able to examine the bull in a way that allows us to admire both its beauty and its ugliness. We cannot help but recall the many myths we learned about as a child when we see imagery of a minotaur in his art. He consciously shows the bull’s history when creating a new image of the bull.

No comments:

Post a Comment